BTB Speaks to

Tilfi

Rooted in legacy but driven by innovation, Tilfi is reimagining Banarasi handloom from the ground up—preserving tradition while building a future-forward ecosystem of trust, dignity, and design excellence.

Written by: Manica Pathak

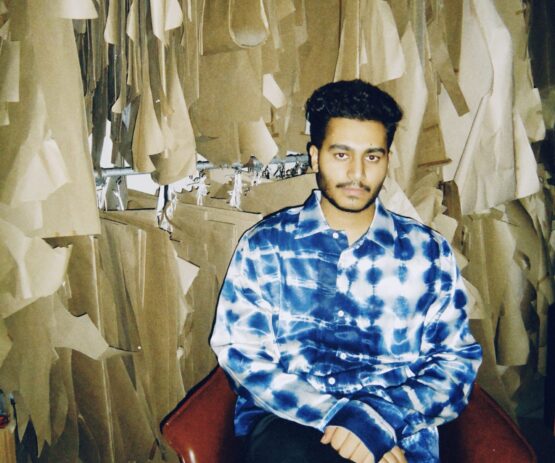

Many contemporary labels in recent years have emerged as natural extensions of textile legacies, handed down through generations. For Udit Khanna too, a legacy in a thriving Banarasi textile spanning over five decades and an inherent entrepreneurial spirit, seemed like a natural recipe for carrying the vision forward. His sights, however, were set on a different path initially. “The family business was something we’d occasionally advise on during our visits to India, because we definitely had a lot of bookish knowledge to offer—but that was it,”says Aditi Chand, Udit’s partner of over twenty years. While she built her career in investment banking, specialising in derivatives, M&A, and growth financing, Udit focused on founding an education company, later acquiring an international English-language school and expanding it to Mexico and Kazakhstan. Eventually, the two joined forces to prepare the company for sale and went on to pursue their MBAs at INSEAD in France.

However, a riveting conversation with a master weaver set them on a new path entirely, or rather guided them back to their legacy. “Every time we were back in India, we’d encourage the weavers to carry their skills forward. Then, during one of those conversations, a weaver turned to us—specifically to Udit—and asked, “You don’t want to continue your father’s trade, but you want me to convince my son to stay in this work? That really stayed with us,” both Aditi and Udit chime in, who later went on to become co-founders of Tilfi, a luxury handloom label dedicated to exquisite Banarasi weaves alongside Ujjwal Khanna Udit’s brother. With a deep appreciation for textiles and an innate understanding of the city’s intricate weaving ecosystem—honed through countless hours at the family’s traditional wholesale store—Ujjwal completed the trio of co-founders and the label’s vision. “It wasn’t about the three founders coming back to do something personal. We knew we wanted to create something that would outlast us—something enduring and institutional which eventually requires a completely different point of view.Our backgrounds in structured, global organizations helped us view this very traditional, often fragmented craft sector through a fresh lens. And because of these life experiences, distinct career paths, and the opportunity costs involved, we approached this with a long-term orientation and a deeper level of commitment,” says Aditi.

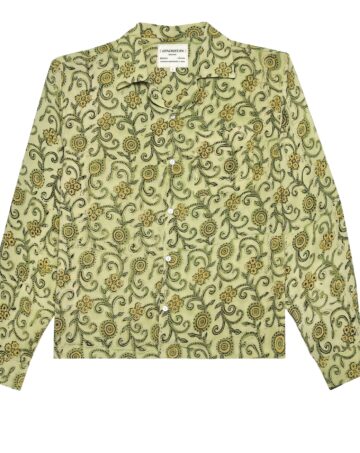

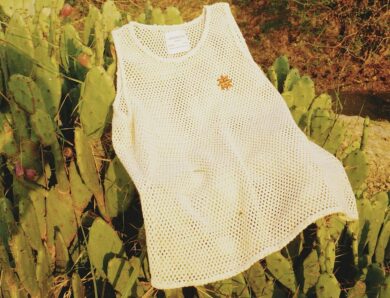

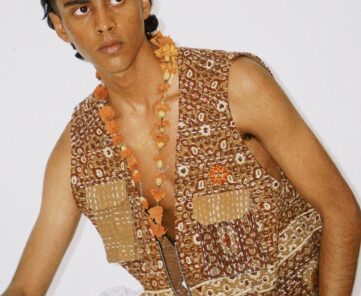

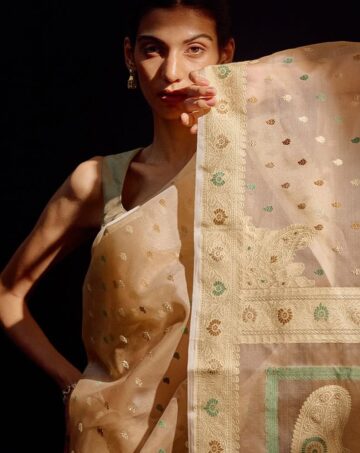

However, for a craft as ubiquitous as Banarasi weaves, “There is this idea that ‘there is too much of Banaras or ‘too many Banarasi brands’. But no one seems to be fatigued by Paris being the fashion or couture capital of the world,” says Aditi . “But the truth is, we need more from Banaras, and from every major craft cluster. We’re working within what is arguably one of the most skilled and vibrant craft ecosystems in the world, with a deeply rooted and highly skilled artisan base. It can’t be confined to a designer’s collection or boxed into labels like ‘traditional’ or ‘heritage’. The craft deserves to be valued for its ongoing evolution,” differs Udits and continues “People also often say that Banaras is stagnant and that there’s no design innovation,” adds Aditi. “But it’s not that they can’t innovate—it’s that it’s risky to do so. Innovation is an iterative process.” she notes and continues, “There’s often a romanticised idea that the weaver does everything, but in reality, the process is far more collaborative. There are several steps before the fabric even reaches the weaver. It begins with a flat paper illustration created by in-house designers, independent artists, and generational designers we work with. Translating that into a woven textile is where the grapher comes in— who plays a key role and interprets the illustration, adding depth and texture to ensure the design translates beautifully onto fabric––so when we talk about upskilling, it becomes about enhancing the skills of everyone involved in the textile creation process. Nothing should happen in isolation. It’s similar to giving ‘stretch assignments’ in the corporate world. You start with simpler weaves and gradually introduce more complex challenges to push boundaries. Early on, we faced a lot of hesitation. The weavers had become risk-averse over the years. Even when we assured them the risk was ours, they’d worry—for us. They’d default to safe choices.” Perhaps for this reason, while Tilfi’s journey has evolved from a modest network of 300 artisans to a thriving ecosystem of over 2,000 highly specialised craftspeople, entrusted with preserving and advancing centuries-old weaving traditions. Yet, this milestone did not come easily. “Many artisans were unsure even though handloom is the second-largest employer in India after agriculture.The hesitation wasn’t just about financial returns—it was also about evolving the craft, envisioning a promising future, and, most importantly, finding creative dignity and pride in their work, which is core to anything handmade. If you’re stuck repeating the same tired language, even if it’s financially viable, it can feel soul-crushing,” Aditi notes, hinting the fact that despite Banaras’ repertoire spanning a gamut of fabrics and weaves, the city is often associated with ‘silks’ and’ brocades’. “But the region is rich in technical specialties—some artisans work only with cotton jamdani, others with satin, koras, or organzas, and these skills have been passed down for generations. Understanding that ecosystem and bringing those specializations under Tilfi’s umbrella took time. We wanted to become a kind of epicenter that nurtured these diverse skill sets,” says Udit.

“Every time we were back in India, we’d encourage the weavers to carry their skills forward. Then, during one of those conversations, a weaver turned to us—specifically to Udit—and asked, “You don’t want to continue your father’s trade, but you want me to convince my son to stay in this work? That really stayed with us,”

So when the founders returned to India and officially registered the brand in 2013, it was about defining Tilfi and its artisans in a way that went far beyond surface-level branding. “One of the first things we wanted to change was the way textiles were traditionally sold,” asserts Aditi and continues, “Previously, the process ran entirely through a wholesale value chain where payments weren’t made upfront. If something was commissioned, traditionally, the weaver would bear the production risk. Whatever didn’t sell, or if a design didn’t work, it would be returned — sometimes 3–4 months later — with payment made only for what had sold. We found this model really untenable. This long value chain, involving wholesalers and retailers, added so many layers that the original story got diluted — like a game of Chinese whispers. Many times, even today, we see artisans create something, and others simply pick it up and sell it. So, by the time it reached the consumer, the narrative was often completely disconnected from the source. It bred mistrust and misinformation,” says Aditi, which led to a fundamental rethinking of the value chain and the relationship between creator and consumer. “We felt that whatever you create should reflect the creator’s voice, and one of the biggest decisions we made was to take on all the risk ourselves, rather than placing it on the weaver, because we believe the person who is most vulnerable in the process should not bear the risk. That’s why we wanted to build something standalone — with a distinctive brand identity and a strong value-based approach, both aesthetically and organizationally. And so, Tilfi came to be.”

Additionally, Aditi draws attention towards how an artisan’s work has historically been shaped by cycles of fluctuation, periods of recognition but often punctuated by long stretches of instability. She notes,“For instance, when a designer or brand places a big order during a particular season, suddenly many weavers get employed.They might even abandon other plans, like spring farming, to focus on weaving. But once the season ends and the collection is done, they’re left with unsold stock and no continuity. These sporadic efforts can be highly disruptive, you need long-term engagement if you want to work with craft ecosystems. Bursts of activity don’t work; the approach has to be intentional and sustained.”

Identifying existing gaps in the industry inspired broader, bolder steps — risky but a worthwhile chance to disrupt a sector that has largely stayed within familiar grounds. “We decided to work across the entire value chain—right from conceiving a textile, imagining what we want to make, to developing and iterating it. We collaborate with our family of artisans to commission and produce the textile, then handle the packaging, marketing, and ultimately place it on our digital and physical shelves.So we own the entire process,” says Aditi. To this, Udit quickly adds,“We also consciously chose not to work with multi-brand stores or resellers. Even though it might offer greater reach, we wanted to control the entire narrative and the story of our textiles—how it’s being told to the end” consumer.” Such an approach is quite telling of how labels like Tilfi are changing the narrative around textile and artisanal communities, “We made a commitment early on, whether or not a design works, the weaver is assured that we’ll off-take and come up with another design. So, the fact that the weaver’s livelihood is no longer tied to whether a design succeeds or fails means they’re more empowered to create and there is a greater willingness to innovate. It’s ultimately a collaborative effort. The trust we’ve built through this system allows for that,” says Aditi.

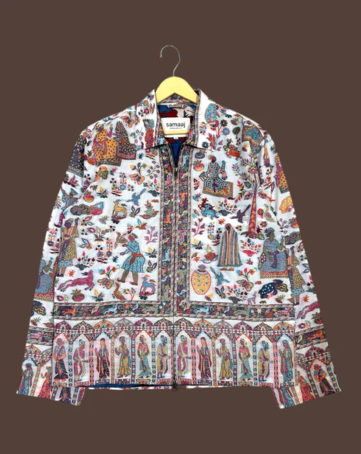

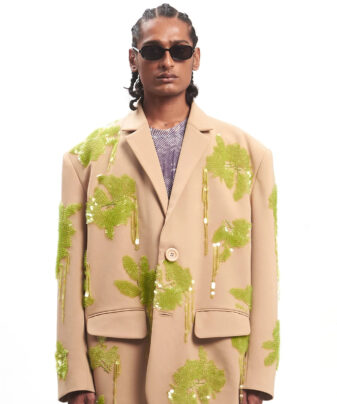

To put things into better context, Udit iterates some of the innovation that the ‘trust’ has allowed for in Tilfi’s creative process. “We created a twill weave in silk for the first time—that’s never been done before on handlooms and produces a very unique textile. Just last year, we wove pashmina along with silk.These are true innovations in craft and we’re actively pushing boundaries,” he says. Another defining milestone for Tilfi, ‘Yatra’ set a new benchmark in the evolution of craftsmanship while celebrating the unmatched artistry of Banarasi weavers. The work now stands as a permanent installation at the prestigious Shilp Deergha in the new Parliament House. “We created a massive, singular woven motif without any repetition — something unheard of in Banarasi textiles,” says Udit. Spanning 32 feet, the handwoven tapestry distills Banaras’ rich heritage, intricately depicting the city’s iconic skyline and landmarks of historical and cultural significance through contemporary Banarasi silk brocade weaving and fine zari embroidery.

As a result, the varying depths and complexities of the challenges faced by the artisan community came into sharper focus, and Tilfi’s mission evolved beyond merely preserving a family legacy. Leveraging their backgrounds felt like bringing together pieces that naturally aligned to address broader systemic gaps. Aditi elaborates, “From setting up communication structures to managing participants, the systems we’ve built internally have been crucial for our growth. Without that structure, I don’t think we’d be able to operate at the scale we do today. It required a lot of our training—maths, finance, our MBA education—it all came into play just to manage the systems and spreadsheets needed.Since everything is decentralized and most artisans weave from their homes, managing such a widespread network requires intentional design. Remote work in this context is complex—it’s challenging to monitor, engage consistently, and navigate the hierarchy. We have weavers and master weavers at different scales: a smaller master weaver might operate 4–5 looms at home, while senior weavers could manage 25–30 looms across entire village complexes. Mapping all of them—and their looms—at the level needed for craft intervention is intricate. One loom might produce satin, another tanchoi, and another something entirely different. We’ve had to map each loom’s exact capability. If we pause a design, we must immediately create a new one that matches both the weaver’s skill set and the loom’s specifications.”

Ultimately, the sustained efforts have yielded lasting rewards. “The economic shift is real, but what’s more rewarding is their desire to stay engaged with the craft. More broadly, thanks to the efforts of many brands, designers, and players in the ecosystem, there’s now a lot more innovation happening. When we started, the space felt stagnant. But today, there’s movement, and that makes us more optimistic,” she says. Along the way, Tilfi has cultivated a discerning portfolio of global clientele and earned the patronage of art connoisseurs worldwide. Yet, the true, holistic revival and sustained growth of the craft — beyond the efforts of individual brands like Tilfi — demands an enduring commitment at multiple levels. “If you search for “Banarasi” online—even though Banarasi has a GI (Geographical Indication)—you’ll still find sarees priced at ₹2,000 in other cities and online platforms being sold under the label ‘Banarasi’. We must protect the provenance of our crafts, and that’s where the government can really step in—by building stronger regulations around this and how they ‘enforce’ it,” says Udit, referring to the institutional framework–at the top of the ecosystem, whose decisions directly influence all stakeholders, from artisans to consumers. Aditi adds in this context, “If there are infringements or violations, there need to be consequences. Otherwise, anyone can label anything however they want—and that creates a lot of confusion for the consumer. In the long run, it’s actually harmful to the craft itself. And I want to be clear—I’m not a purist or traditionalist in that sense. I have no problem with machine-made saris or textiles. But they shouldn’t be misrepresented as something they’re not.” And for those on the receiving end of the process—the consumers, “It’s more about the perception about the craft.’Do you see it as something that needs uplifting and saving, or do you see it as something that’s akin to art?’ That perception makes all the difference.” says Udit and continues to note, “The most important thing to remember is that craft should not be treated as charity. Our artisans are not people who need sympathy—they need patronage, and more importantly, admiration. They are creative professionals, just like us, and like everyone else involved in bringing this work to life. What the craft ecosystem really needs are platforms to showcase creativity—not just support to sell or market access.”

Ultimately, the future of the craft also depends on how businesses choose to build within the ecosystem and the approach they take to sustain it meaningfully.“For me, it would be orientation. I feel like Indian businesses, especially in the D2C space, often focus on funding and fast growth. But when it comes to craft, the way we build needs to be different—it requires a long-term orientation. People need patience and a vision to create something of real value. My singular advice, especially for craft-based businesses, is to go deep—truly understand the craft until you gain a level of expertise. Only then can you innovate. So, it’s about building deep roots, thinking big, but staying grounded in the long term,” says Udit. “And that applies not just to craft, but to any kind of venture. The first and ongoing priority should be to develop a deep understanding. Without it, you’re just chasing something transient,” concludes Aditi.