BTB Speaks to

Samaaj

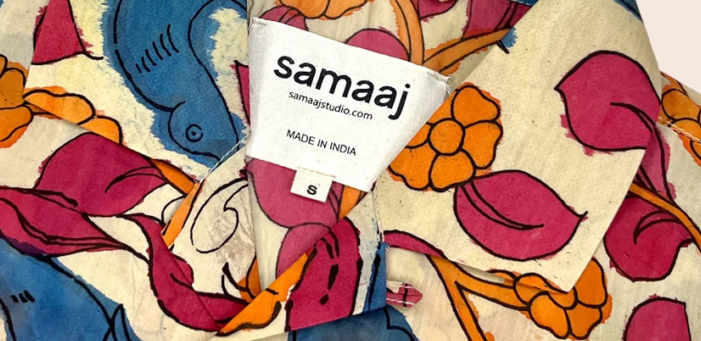

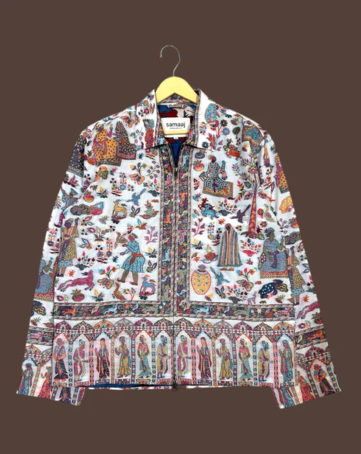

Raman Chawla founded Samaaj in 2023 as a contemporary menswear label, blending traditional Indian craftsmanship like Kantha, Kalamkari, and Pashmina with modern silhouettes, fostering direct collaborations with artisans and upcycling vintage textiles to create culturally rich, sustainable fashion.

Written by: Manica Pathak

Sometime in 2021, Raman Chawla, then a footwear design student in India, decided to pivot his path, moving to Montreal to study Fashion Marketing. “When you’re abroad, there’s a stronger urge to connect with your roots and showcase your culture,” he says, recalling the year when, as part of his curriculum, he had returned to India to work with artisans in Bagru, for a research project. But what began as a small research initiative soon evolved into a personal creative endeavour. It wasn’t long before—following appreciation from his friends—Raman found himself making frequent trips back to Bagru, this time to experiment further with silhouettes. “I posted the outfits on a subreddit called Streetwear Startup. To my surprise, the post blew up! People were so interested in the pieces and the story behind them—the natural dyeing and block printing really captured their imagination,” notes Raman on this exploration that marked the first steps toward launching his own contemporary menswear label in 2023, which currently offers a line-up of shirts and jackets in crafts including Kantha, Kalamkari and Pashmina.

Gradually, things have picked up for Samaaj since, having amassed a significant following on social media alongside prominent celebrities donning the label’s outfits. But what’s even more fascinating about Raman’s journey is his independent pursuit, having travelled and nurtured relationships with handloom weavers from Andhra Pradesh, Bengal, and Gujarat. During these visits, Raman is someone who has always followed a thoughtful approach. “Since they might not always work with the same professional processes I’m used to, I make sure to set clear expectations, especially to achieve a specific quality. First, I look at what they’ve made in the past—any references I can gather from their work. I then explain my ideas to them, often word by word. If needed, I create a tech pack or detailed drawings to make things clearer and print them out for reference.”

“Since they might not always work with the same professional processes I’m used to, I make sure to set clear expectations, especially to achieve a specific quality. First, I look at what they’ve made in the past—any references I can gather from their work. I then explain my ideas to them, often word by word. If needed, I create a tech pack or detailed drawings to make things clearer and print them out for reference.”

But even today, having worked with several indigenous communities as Raman runs his label from his hometown in Delhi, he makes sure that he taps into resources with suppliers where inventory is abundant but often goes to waste. “In Delhi, there’s a Gujarati society near Connaught Place where many Gujarati women sell their vintage pieces as a side business. I source most of the patchwork fabrics from there. I also have a supplier in Kolkata who provides us with Kantha fabrics. For Kashmiri shawls, I got in touch with a supplier I found through one of the government-run initiatives.”

Hand Embroidered Collection

He also makes it a point to visit the right places, “The government here is very proactive in supporting artisans. Many government buildings host small shopping centres where artisans promote their crafts. Places like Pragati Maidan and Dilli Haat are prime examples—every week or two, a new batch of artisans showcases their work, and the government covers their travel and other expenses. I make it a point to visit these places regularly. I collect their contact details and sometimes take samples from them. If I need custom pieces made from scratch, I visit their workshops directly.”

Although here Raman has picked up on an irony. “Whenever I visit markets in Delhi where artisans showcase their work, it’s often disappointing to see that the main attraction for visitors is the food stalls rather than the crafts or clothing,” he says. This neglect, according to Raman, can be attributed to, “In India, they are so ubiquitous. We have grown up surrounded by these crafts, so they don’t intrigue us as much as they might intrigue someone encountering them for the first time.” he says. Even garments made from upcycled fabrics—one of Samaaj’s key offerings, where vintage deadstock materials from decades ago are transformed into outerwear and shirts—often face stigma. “For domestic stockists, especially in places like Mumbai, we’ve received feedback that customers don’t like visible signs of wear, patches and fading preferring items that look new and untouched. It’s a common challenge in India.”Their value is further overshadowed by mass-produced alternatives, “I’ve faced a lot of backlash from the domestic market for pricing. People often comment things like, “Why is this so expensive? I can get this cheaper elsewhere. Because it’s so easy to replicate hand-block prints through screen printing. People are used to paying ₹100 per meter for those, so it becomes very difficult to sell one piece for ₹10,000 or ₹15,000 in India.”

However, labels like Samaaj have managed to garner substantial attention across borders. “Internationally, especially in markets like the US and Europe, there’s a high level of interest in artisanal, sustainable, and culturally significant products. Indian crafts are often perceived as exotic, and people really appreciate the unique stories behind them. For example, at a pop-up I did in Mumbai during the Boiler Room Festival, the UK team was fascinated by one of my Kalamkari hand-painted shirts, amazed to learn that the entire piece was hand-painted with a brush using natural dyes.”

This renewed appreciation for crafts and textiles must find its way back home.“The handloom and sustainable textile industry often caters to a privileged section of society because of its cost. But these crafts are expensive to produce, and that naturally reflects in the pricing of the products.” Eventually, a few recalibrations are due—and the timing couldn't be more serendipitous, with conversations around textiles and crafts gaining momentum and young labels taking bolder strides in their representation, “Making these crafts more accessible to the masses while ensuring that the actual artisans, rather than middlemen, benefit could help promote the craft. Perhaps subsidies or tax rebates on handloom fabrics could make these products more affordable. Lower prices could help reach a wider audience and bring more support to the artisans themselves,” Raman concludes.